ACRYLIC ON CANVAS • 24″ x 18″

Sold • prints available; email julie@juliemeridian.com to buy prints ⇢

Reel-to-Reel is the sixth of seven technologies I’ve explored in Prior Art: analog media manipulation and vintage virtual reality.

Chris Edits the Clips

“Software has eaten music production. It’s gotten much cheaper, more dematerialized, and extremely powerful. And it’s become sterile, automated, and over-produced. My work tries to make digital music seem analog, to blur the 1s and 0s with waves and voltages, noise and decay. When I see these Old School reel-to-reel tapes I hear the room noise hissing like electric snakes on a Summer lawn, the rich magnetic warmth of tape head transduction, and the slight aperiodic wobble of the motors resolutely unknowable in the face of unyielding digital perfection.”

Chris Arkenberg // @chris23 // harryselassie.bandcamp.com

Early audio used cylinders or disks to capture recording, until the middle of the 20th century when advances in tape recording provided a higher fidelity than ever before. Recordings were primarily made onto tape until the advent of digital recording. Tape recording allowed performers, who previously could only perform live, to record and edit their shows. It also enabled producers to create multi-track recordings where individual performers could record their parts and the producer could have greater control over how they combined into the final recording.

Recording studios used reel-to-reel tapes to capture individual performances and layer sounds. It also enabled editors to include sound effects like laugh tracks. In addition to the dedicated recording studios, radio stations would often have their own sound recording and mixing equipment as well. This was used for recording interviews and live performances at the station. It was also a way to create advertisements or underwriting spots that were pre-recorded and could be played between songs

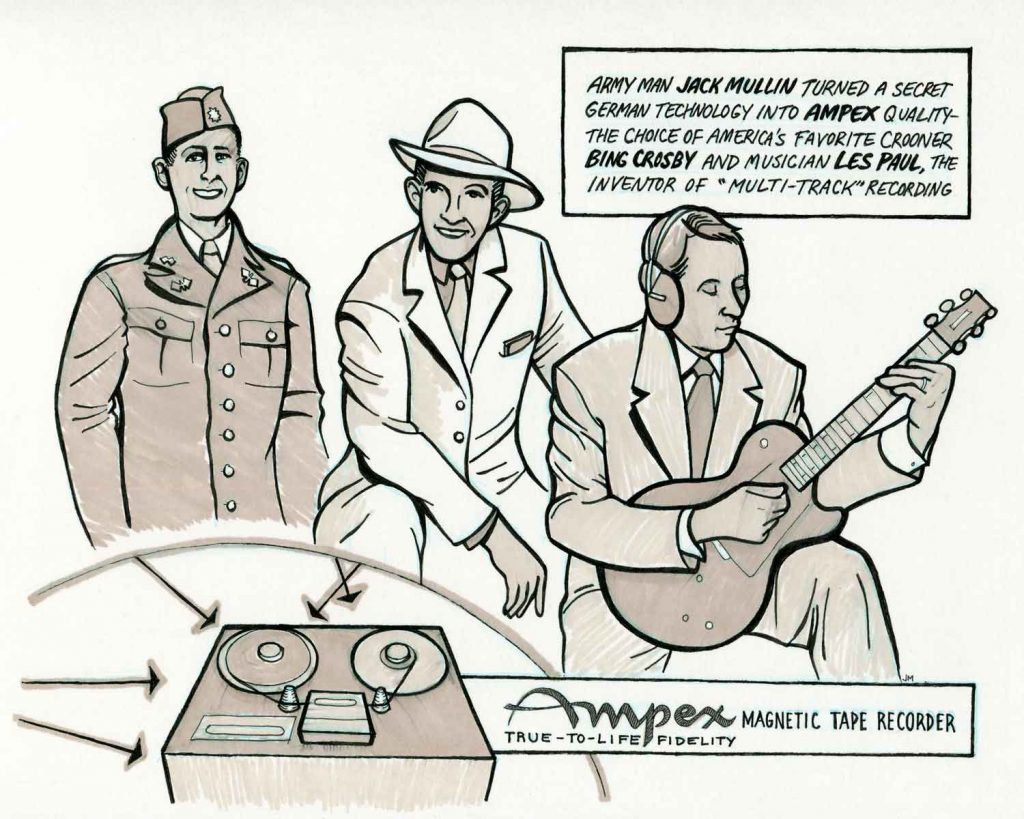

True-to-Life Fidelity

Advances in tape technology were a closely-guarded secret during World War II. German engineers had accidentally discovered a much higher-fidelity form of recording than previously thought possible, and this was used to allow Hitler to broadcast supposedly “live” speeches from other cities. At the end of the war, U.S. Army Signal Corps member Jack Mullin came across two Magnetophon machines at a radio station in Frankfurt that he brought back home and reverse-engineered to develop the machines for commercial use.

One early adopter was Bing Crosby, who was a popular radio star who had grown weary of a live recording schedule. He saw the potential in pre-recording shows and promptly invested in the technology, becoming the first American performer to use it. Further development led to stereo and multitrack audio recorders. One of the first musicians to use those was Les Paul who also invented the electric guitar. These two inventions set the stage for the explosion of rock and roll music.

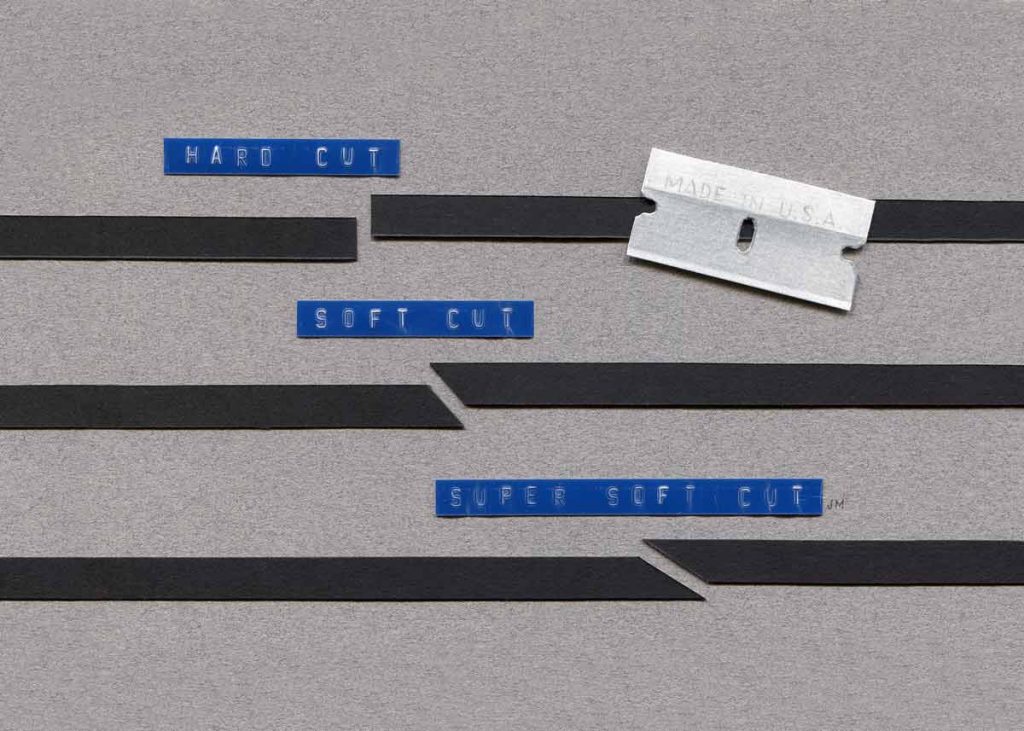

The Art of Splicing

Editing a reel-to-reel recording is a manual process of cutting and combining tape. Some machines included tape splicers directly on them, but editing could also be done simply with a steady hand, a sharp blade, and tape.

The angle of the cut affects the nature of the transition. A “hard cut” is a strict transition from one tape to another where the tape is cut at a 90-degree angle. For a softer transition, editors use a “soft cut” of 45 degrees or a “super soft cut” of 30 degrees.

Leave a Reply