ACRYLIC ON CANVAS • 18″ x 24″

$1200: Marcela Animates • Email julie@juliemeridian.com to buy this artwork ⇢

Zoëtropes are the third of seven technologies I’ve explored in Prior Art: analog media manipulation and vintage virtual reality.

Marcela Animates

“As a storytelling device first and foremost, I was always drawn to how animation can capture energy, possibility and emotion all at once…and in the most fantastical way. To paraphrase Steven Spielberg, ‘…with animation, fantasy is your friend’.”

Marcela Cordon // Instagram: @cordon3

Though progressions of drawings to indicate movement have been around for a millennium, the technologies to animate them developed rapidly in the late 19th century leading up to the advent of film. One of the first was the phenakistoscope (or stroboscope disc, or phantasmascope) in 1833. This arranged drawings radially on a disc, though its inventor Simon Stampfer imagined they could also be on a cylinder or loop of paper/canvas. Later inventions improved on this with similarly colorful names: the dædaleum, the zoëtrope, the praxinoscope, and the zoopraxiscope.

Zoëtropes have been built small enough to be held in one’s hand, and large enough to hold hundreds of people within them. Typically a zoëtrope can be viewed by multiple people at once since the slits surround all sides of the cylinder. More recently, artists have created 3D zoëtrope animations (using sculptures instead of drawings) and subway zoëtropes (using the motion of passing trains).

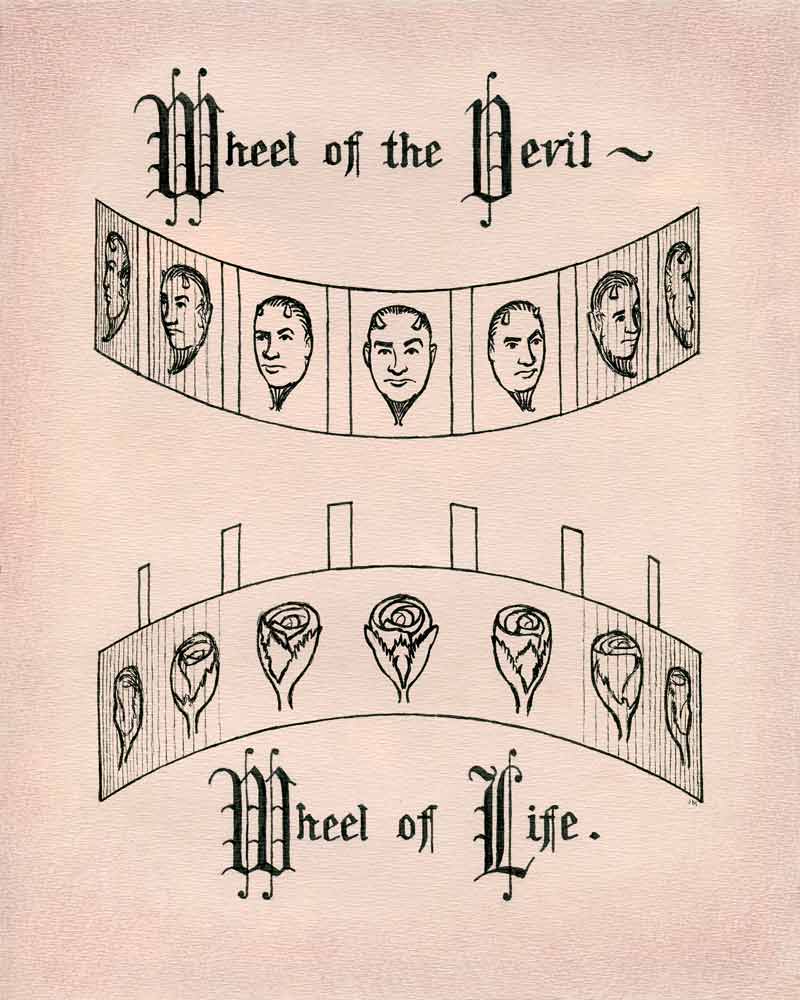

Wheel of the Devil ~ Wheel of Life

William Horner, inventor of the dædaleum, described his invention “as imitating the practice which the celebrated artist of antiquity [Dædalus] was fabled to have invented, of creating figures of men and animals endued with motion.” It’s unclear whether the name (which also translates as “cunning one”) or the content (one popular animation had a devil in it) led to its nickname: the “Wheel of the Devil”.

A Milton Bradley employee, William E. Lincoln, improved upon the invention by shifting the viewing slits up so that new strips of animations could be easily swapped out. In a savvy marketing turn, he also called his invention the “zoëtrope” which translates to “Wheel of Life” – a much more family-friendly name.

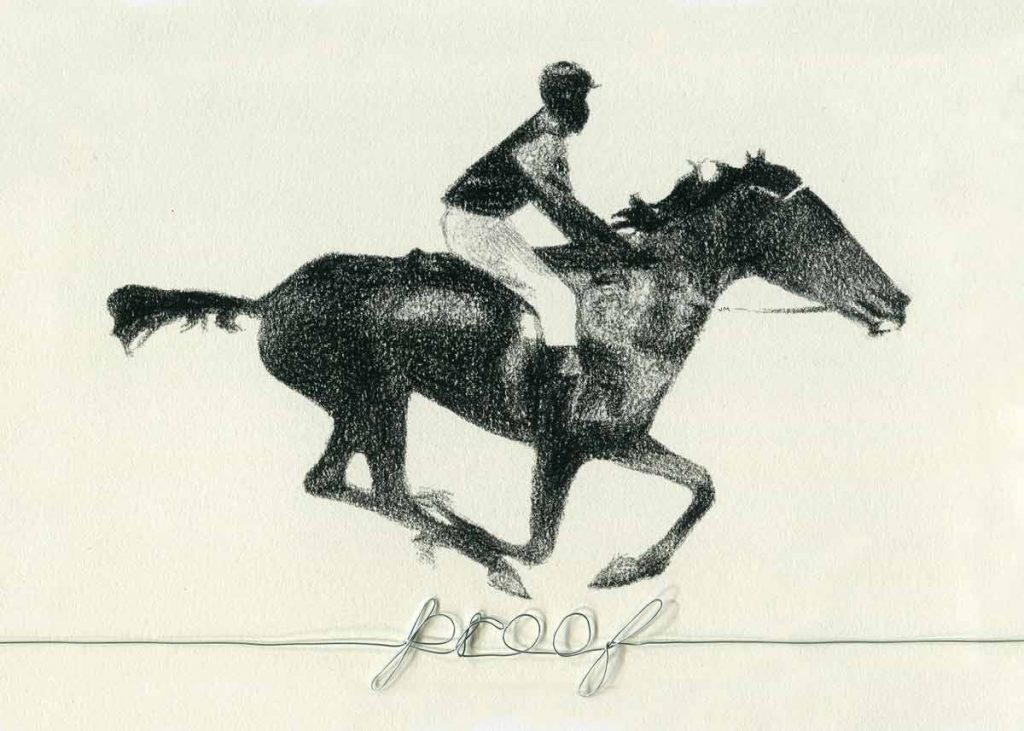

Muybridge’s Proof

Before film could capture motion, no one could prove for certain how particular motions occurred. Eadweard Muybridge, a photographer, was commissioned in 1872 by Leland Stanford to photograph horses to help settle a $25,000 bet as to whether a racehorse’s hooves all leave the ground at once when running.

After years of technological and personal setbacks, Muybridge succeeded in rigging a series of specially-designed equipment with tripwires to rapidly capture a series of images documenting one full gallop. Two of those sixteen images definitively revealed that all four hooves were off the ground. Muybridge spent the rest of his life improving on this technique for creating motion studies.

Leave a Reply